Thursday, January 22, 2026

South African High Schools & the “Billboard Test”: Why Our Digital Narratives About Young People Are Outdated & What We’re Missing

Authors Note:

Lisa Adams is the Founder of Citizen Code, an African–based technology collective building inclusive digital products for social impact. She has led the design of youth-focused platforms, AI-enabled chatbots, and web ecosystems that reach millions of young people across Africa and East Asia, with a strong focus on gender justice and digital equity.

She frequently speaks and writes on tech-facilitated gender-based violence, feminist approaches to technology leadership, and the intersection of heritage, culture, and innovation. Lisa represented Civil Society at the W20 pre-panel on the Future of STEM ahead of the G20, bringing her perspective as a technologist and advocate for accessible, community-rooted digital futures.

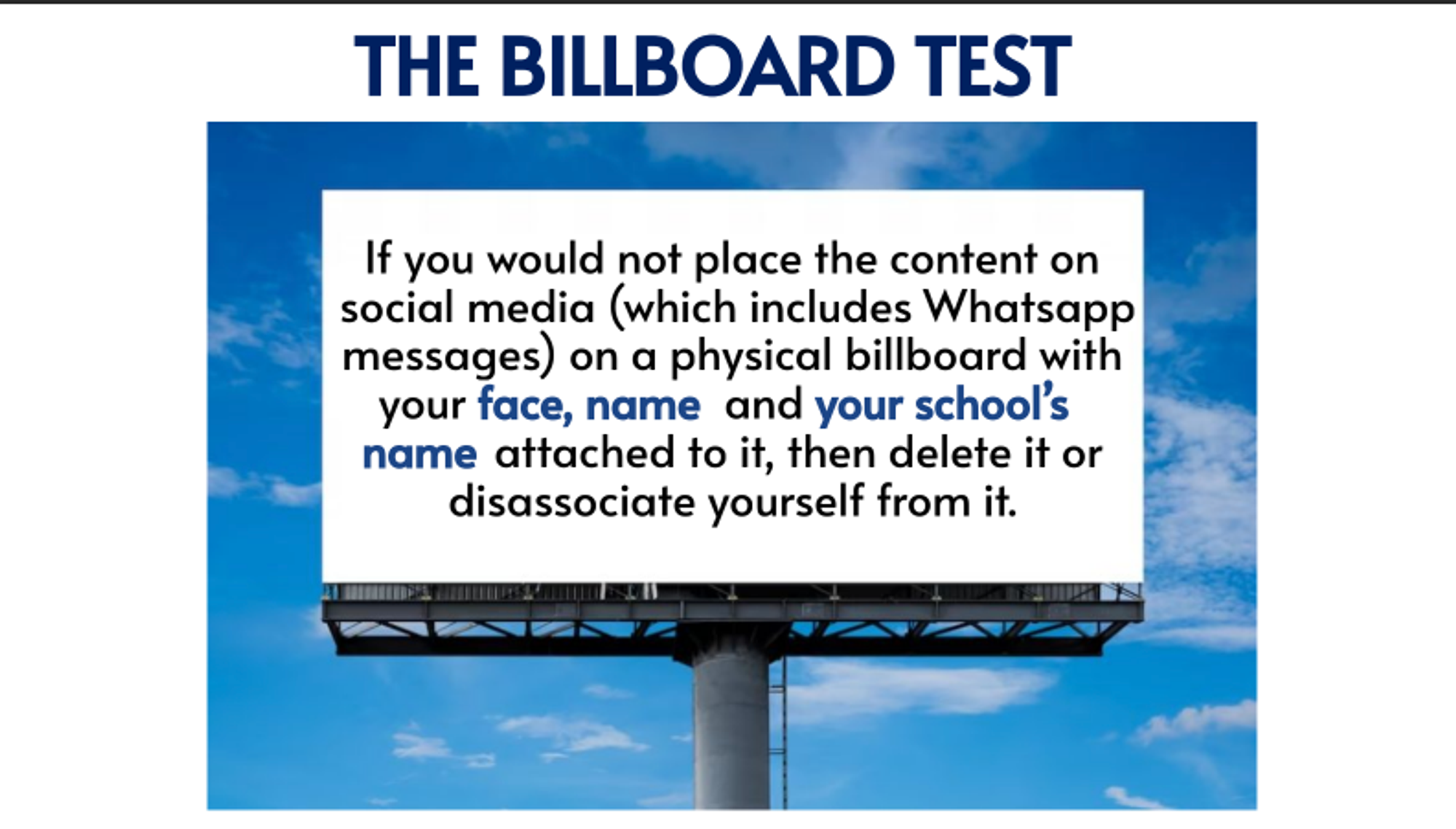

I was sitting in a school meeting recently, next to my teenage daughter, listening to a framework the school has been using to guide learners’ behaviour online. It’s called the “Billboard Test.” The idea is that if a young person wouldn’t be comfortable seeing a message, image, or post displayed on a public billboard with their name, face, and school attached to it, then they shouldn’t post it online at all.

On the surface, this sounds sensible. A pause button. A reminder that digital content can travel. But as it was explained again, I felt a growing sense of discomfort. Not because I disagree that young people should think before they post, but because this framing reveals a much deeper problem in how we, as adults and institutions, understand young people, technology, and power.

I come to this conversation wearing multiple lenses. I am a gender justice and social impact technologist. I design digital platforms for young people across Africa and globally, often in contexts where digital spaces are not just social, but protective, educational, and sometimes life-saving. Much of my work focuses on youth platforms that support mental health, sexual and reproductive health, gender-based violence response, and access to care. I am also a mother to a teenager, and I participate in national youth dialogues, including spaces like Parliament, where young people articulate their realities with depth, political awareness, and clarity.

So when schools talk about digital safety, I listen closely.

What struck me in this meeting was not only the Billboard Test itself, but the tone surrounding it. There was a strong undercurrent of fear around cellphones and social media. One teacher joked openly about owning the password to her teenage son’s phone, about how he blocks her from viewing his WhatsApp statuses, and how she regularly logs into his phone to check and unblock herself. The room laughed. I didn’t.

Instead, I found myself asking where we are drawing the lines around privacy, trust, and agency for young people, and whose anxieties we are actually managing when we default to surveillance.

There is no question that real digital risks exist. Deepfakes are real. AI-generated impersonation is real. Harassment and exploitation are real. As someone working at the intersection of technology, ethics, and gender justice, I take these risks seriously. But acknowledging risk is not the same thing as governing through fear.

The Billboard Test collapses all digital interaction into the most extreme version of public exposure. A billboard is permanent, stripped of context, and governed by adult norms. But this is not how young people experience digital life. Their online spaces are layered, relational, and often intentionally semi-private. These spaces are where they form language, humour, identity, belonging, and peer culture. Treating every message as if it were a public billboard ignores this reality, and young people know it.

What often goes unspoken in these conversations is that young people are not simply using new tools. They are participating in a newer form of expression. Statuses, disappearing messages, close-friends lists, emojis, memes, and coded humour are not reckless behaviour. They are contemporary social language. When adults flatten this into “would you put it on a billboard,” we erase nuance and context, and the message lands as control rather than care.

Sitting next to my daughter, we exchanged looks. Later, we spoke about how strange it would feel for me to simply own her passwords or limit her ability to express herself digitally, when my approach as a parent has been to do something different: equip her with knowledge, boundaries, and confidence so she can navigate these spaces herself. Not perfectly. Not without mistakes. But with trust, conversation, and support.

Privacy is not a luxury for young people. It is a developmental need. For girls, queer youth, and marginalised young people in particular, privacy can be protective. In my professional work, I have seen how digital safe spaces allow young people to ask questions they cannot ask at home, at school, or in their communities. I have seen how anonymity enables honesty, how controlled visibility can support mental health, and how peer-to-peer digital spaces can reduce isolation rather than create it.

There is another layer missing from most school-led digital safety conversations, and it is one we intuitively understand in every other area of human development: how people learn.

As humans, we do not learn primarily through warnings and restriction. We learn through play, experimentation, rehearsal, failure, and trying again in spaces that are safe enough to absorb mistakes. This is why children play. It is why we use simulations to train pilots, doctors, and engineers. It is why mock parliaments, role play, and debate exist. We have always understood that people need low-risk environments to practice high-stakes decisions.

Digital life should be no different.

In my work designing youth-facing digital platforms and impact games, we don’t assume young people will always make the right choice. We design with the understanding that they are learning. That means building spaces that allow young people to practice decision-making before the stakes are high. Our sexual and reproductive health chatbots, for example, are not only about access to information. They allow young people to rehearse conversations, understand options, practice consent, learn about health behaviours, and seek support privately before navigating these realities in the world.

These digital tools function as simulations. They create room for reflection without punishment, learning without exposure, and growth without shame.

What concerns me is that fear-based frameworks like the Billboard Test remove this possibility entirely. They don’t teach discernment. They teach self-censorship. The unspoken message becomes: if there is any risk at all, don’t speak. Don’t post. Don’t experiment. Don’t be visible. That message does not land equally for all young people, and it reinforces already unequal policing of expression.

There is also a deeper contradiction here. As social impact technologists, educators, and youth practitioners, we invest in digital platforms precisely because they work. We know young people meet us there. But when schools frame digital engagement as inherently dangerous, they undermine the very tools designed to support young people’s wellbeing, learning, and agency, and they do so in front of the parents and gatekeepers who influence access.

So the question becomes not whether digital life is risky, but whether we are willing to update our frameworks to match reality.

Instead of outdated metaphors, schools could be teaching layered decision-making. Instead of surveillance, they could be modelling trust. Instead of punishment, they could be introducing guided digital tools and classroom-level digital assistants that help young people think through real scenarios, understand consequences, recognise power dynamics, and know how to seek help or repair harm when things go wrong.

The digital age is not something young people need to be shielded from.

If we want young people to be safe online, we need to stop teaching them to disappear, and start teaching them how to navigate visibility, expression, and power with confidence.

Join us in building digital solutions as a foundation for lasting change.